A 6-year-old in Leila Lubin’s classroom wouldn’t budge from his seat. The rest of his peers had filed off to their enrichment classes but he refused to move. He wasn’t done with his work and he didn’t want to go.

Lubin, a champion of behavior management and crisis prevention training for teachers, knew what to do. She turned to a script that has become such a routine part of her classroom that it seems to elicit an almost Pavlovian response – steering misbehaving students back on track at the sound of the words: “Aw man, you’re having a really rough time right now. We’re going to do some learning later.”

This time, it didn’t work. “Boom. Explosion,” Lubin said recently, recounting the episode. “‘I don’t want to learn later! I don’t want to practice with you!’ ”

Teachers at all grade levels see some version of this in their classrooms. The catalyst or the nature of the disobedience may change, but the core issue remains. What are they to do?

In some parts of the country, teachers in Lubin’s position pull out a paddle.

5 percent of teachers are responsible for more than one-third of all office discipline referrals, according to a study of one large California district.

Punitive school discipline is rampant in the United States, whether it’s corporal punishment or, much more commonly, suspensions. Students lost more than 11 million days to out-of-school suspensions during the 2017-18 school year, the last federal count, and they spent many times that number in in-school suspension rooms, kept from the classrooms where their teachers were teaching. Black students face more than their fair share of this punishment, as do boys.

Teacher burnout is at record highs, and surveys continue to show that educators believe student behavior is worse than it was before the pandemic. With everyone in school buildings stretched to their emotional limits, some districts across the country have been suspending students even more.

“This is not only a big problem, but a pivotal one,” said Jason Okonofua, a psychologist at University of California Berkeley who studies school discipline. “It changes children’s entire lives – and also teachers’ in leaving the profession.”

Related: Some kids have returned to in-person learning only to be kicked right back out

Critics point out that punitive discipline doesn’t teach students the skills they need to behave differently – like how to manage their frustration when the bell rings and they’re still working. And it creates new problems: Students who get suspended generally do worse in school, graduate at lower rates and are more likely to have run-ins with the police. Reducing suspensions has become a national goal, but some schools have cut corners, simply removing the option without changing much else, and thereby leaving teachers overwhelmed.

What schools should do instead, experts argue, is help educators learn how to pre-empt the behavior that gets students punished. Ultimately, students are wild cards. But the adults leading schools can both control themselves and enough of the student experience to prevent misbehavior. When that isn’t enough, as in Lubin’s classroom so recently, educators can assign consequences that offer empathy and aim to teach, rather than punish.

“Even really difficult kids are actually using positive behaviors 90 percent of the time.”

Scott Ervin, creator, Behavioral Leadership model

That’s ultimately the path Lubin chose.

First, she gave the boy a couple minutes to calm down while she busied herself in the classroom. When he was ready to hear it, she got to the point: He couldn’t refuse to put his work away. She understood his frustration, but he needed to control it.

Lubin sent the boy to his next class so he wouldn’t miss any more instruction, but later in the day, when the rest of his peers were choosing their own activities, Lubin had him sit down and simulate being interrupted in the middle of his work. The boy’s consequence for his morning misbehavior was four run-throughs of a frustration-free transition.

The Greater Dayton School, where Lubin is a founding teacher, doesn’t assign suspensions. Educators at the private, tuition-free school for students from low-income families are trained and coached to avoid doing so. “What we want to do is create that love of learning,” Lubin said. “If a student is sent home every time they do something wrong, they’re going to grow up not really liking school.”

The more Lubin has studied behavior management techniques during her five years of teaching, the more second-nature her responses have become – and the more effective. Sticking to her scripts, armed with information about child development and the nature of behavior, she has seen real change.

“If I’m calm, if I’m mindful, empathetic, if I’m showing verbal and nonverbal signs of calm, I can actually calm you down, too.”

Susan Driscoll, president, Crisis Prevention Institute

“It transforms the classroom,” she said.

The model the Greater Dayton School used this past year is called “Behavioral Leadership.” Its creator, educational consultant Scott Ervin, began developing the approach as a teacher. After, that is, he spent his first two years yelling himself hoarse trying to keep his students in line.

Like other successful approaches, Behavioral Leadership emphasizes the power adults have over children’s behavior. And as Ervin so painfully learned in his early years of teaching, that power is most effectively wielded quietly.

Related: ‘State-sanctioned violence’: Inside one of the thousands of schools that still paddle students

While Lubin found most of Ervin’s strategies easy to implement, she struggled with his advice to quickly move past misbehaviors. Ervin recommends teachers spend more time pointing out good behaviors than bad ones, creating incentives for students seeking attention to behave properly.

“Even really difficult kids are actually using positive behaviors 90 percent of the time,” Ervin said.

He advises teachers to take only the briefest pause from instruction to acknowledge bad behavior and to always do it with empathy – “Aw man, you’re having a really rough time right now.” True to her training, Lubin followed those statements up with a comment about “doing learning later,” something that would take up Lubin’s time, but be more of an investment than a cost. As the school year went on, for example, the student who refused to stop working got better at transitions and learned something about managing his emotions. And that, overall, saved Lubin time.

“What kids are rebelling over is compliance and boring instruction.”

Michael Toth, founder and CEO, Instructional Empowerment

Along with Ervin’s techniques, Lubin had other training to draw on – a model designed by the Crisis Prevention Institute. The institute trains teachers on de-escalation techniques grounded in brain science. Student outbursts and defiance are often unthinking responses, not calculated ones. Kids are emotional and acting emotionally. While teachers can’t control students’ behavior, Susan Driscoll, president of the institute, insists they can affect it.

“If I’m calm, if I’m mindful, empathetic, if I’m showing verbal and nonverbal signs of calm, I can actually calm you down, too,” she said.

Perhaps counterintuitively, being mindful and empathetic can come down to maintaining a level of emotional detachment. Student misbehavior can feel like a personal attack to teachers.

School District U-46, a 36,000-student district west of Chicago, has used CPI training for almost 15 years to help teachers retain their calm and remain empathetic. Mark Gonnella, an assistant principal who has trained his colleagues on CPI strategies at an elementary, middle and high school in U-46, finds that “rational detachment” element to be crucial.

“We as adults, we have to separate ourselves from that situation and not take things personally in order to help these students,” he said.

Such separation can help teachers develop and preserve supportive student relationships, which, in themselves, can lead to calmer classrooms. Okonofua, the UC Berkeley psychologist, has drawn clear connections between a lack of empathy for certain types of students and more frequent discipline of those groups. Okonofua tested what he now calls “Empathic Instruction” through real-life experiments and said he saw repeated success. The approach not only resulted in a reduction of total school suspensions, but also reduced disparities in school discipline for Black students, boys, and those with disabilities.

“It seems to work surgically well specifically for the groups that are at heightened risks of getting in trouble,” Okonofua said. “It’s especially beneficial for them and it’s because they were the ones least likely to receive that empathy or that benefit of the doubt.”

Related: Many schools find ways to solve absenteeism without suspensions

Okonofua’s model asks teachers to spend less than an hour online at the beginning of the school year, reflecting on the power teachers have to help students, especially when they misbehave.

“Most educators join the profession because they want to help children learn and grow and become their best possible selves,” Okonofua said. “It’s about tapping into what’s already in their hearts and minds.”

And just as adults have control over themselves, they also control much of the student’s school experience. Experts say clear and reasonable behavior expectations are critical to well-functioning schools. These expectations should be consistent across all parts of the school so students don’t have to manage major shifts over the course of their day.

Last year, teacher Tony DeRose worked as a behavioral coach at Glenwood Middle School in Findlay, Ohio. He crisscrossed the school, consulting with teachers on issues in their classrooms, monitoring the school entrances and hallways, and, perhaps most dramatically, transforming the lunchroom.

“When I first walked in there, I was like, ‘This is craziness. It’s not safe. It’s not enjoyable,’” DeRose remembered. Students were being bullied, they were yelling and cursing, and the standard response was to send troublemakers to the office for discipline.

DeRose created new structure to the lunch period, setting new rules for when students could leave their tables, requiring clean language and quieter speech, and projecting optional conversation prompts onto a screen including “would you rather” questions and brain teasers. DeRose also handed power back to students, creating a student volunteer corps – another element of Ervin’s behavioral leadership program. Well-behaved students were deputized to dismiss tables at the end of the period and plan activities for recess.

Very soon, no students needed to be sent out of lunch for discipline, DeRose said; the total number of office referrals schoolwide dropped by 26 percent.

Related: Hidden expulsions? Schools kick students out but call it a ‘transfer’

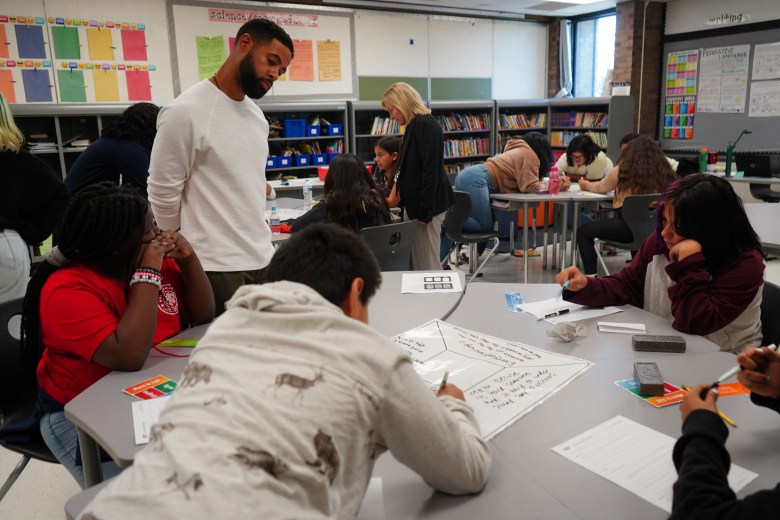

Of course, educators exert the greatest influence over students through teaching. Planning engaging learning experiences, then, is arguably the most powerful way to keep students from misbehaving. Students who are focused on class activities don’t have time to misbehave. In Illinois’ U-46, a post-pandemic focus on improving classroom instruction is expected to improve student behavior, too. The underlying model, developed by an organization called Instructional Empowerment, emphasizes making students more active participants in classroom instruction, working in groups, talking and thinking through lessons rather than simply sitting and listening to lectures.

“What kids are rebelling over is compliance and boring instruction,” said Michael Toth, founder and CEO of Instructional Empowerment. His organization works primarily with high-poverty, low-performing districts and trains teachers to offer kids more rigorous, engaging learning opportunities. As he has guided schools through the transformation, he has seen behavior problems drop precipitously.

“If a student is sent home every time they do something wrong, they’re going to grow up not really liking school.”

Leila Lubin, founding teacher, The Greater Dayton School

But the fact is, kids will continue to act out. Just as they are learning about science and math and history, they are learning how to control their emotions, how to interact with their peers and how to respond to unexpected challenges. Every now and then, they won’t do it right. And if every child, every now and then, erupts, that means a lot of potential outbursts in any given school over the course of the year to which educators must respond.

As evidence of the negative consequences of punitive discipline continues to pile up, there is greater urgency to find alternatives. Schools, however, face a cultural challenge in making this shift. Despite the negative effects of suspensions and the studies that say they don’t work to change behavior, teachers, parents and even students want to see kids face consequences for misbehaving.

Changing school culture can be painstaking work. Even Illinois’ U-46 saw its suspension rate climb from 6 per 100 students before the pandemic to 8 per 100 last year. Lela Majstorovic, the district’s assistant superintendent, said expanding CPI training and helping teachers and other staff members manage student behavior is a priority going into the 2023-24 school year.

“This is not only a big problem, but a pivotal one. It changes children’s entire lives – and also teachers’ in leaving the profession.”

Jason Okonofua, professor, University of California Berkeley

Studies show schools can also offer targeted support to teachers who most frequently send students to the office and have an outsized impact on overall discipline rates. Researchers from the University of Maryland College Park and the University of California Irvine recently found 5 percent of teachers in a California district were responsible for more than one-third of all office discipline referrals – and their overreliance more than doubled the Black-white gap in such discipline. Helping just those few teachers better manage and respond to student behavior can not only drive down total school discipline but the pernicious disparities researchers have been tracking for decades.

Lubin has been a voracious consumer of new approaches to maintaining order and calm in her classroom. This summer, she is strategizing how to teach students specific techniques for regulating their emotions and how to help them choose the right methods in the moment. She finds all of the models she has studied flow together well and just wishes more schools incorporated them.

“We don’t need in-school suspension, we don’t need to send kids home, because they’re missing out on instructional time,” Lubin said. “There is no point of that.”

This story about misbehavior in classrooms was produced byThe Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.